No, You Don't Hate Sweet Wines

You just associate sweetness with shitty wine.

A few days ago, I realized I had a Tupperware container sitting on my countertop with my mom’s handmade Xmas fruitcake in it.

From LAST YEAR’S Xmas.

It had been sitting on my counter, at room temperature, even through the hot summer months, in my non-AC’d kitchen, for a solid year. Wrapped in parchment and inside a Tupperware container but that wouldn’t stop it from getting an STD.

Against my better judgment, I unwrapped it. It smelled pretty good. I cut into it. It looked pretty good. I took a bite.

Holy shit, it tasted pretty good!!!

It was dried out, but otherwise tasted as though it had just been made. I poked holes all throughout with a toothpick and drizzled an additional coating of rum overtop it. Then re-wrapped and let it sit for a couple more days. Rehydrated, and re-boozed, it was literally like it had just been made yesterday!

Sweet Wine is the Fruitcake of Wine (Wait! You Still Don’t Hate It!)

You’ve simply never had well-made versions of it.

Cheap fruitcake (or “puddings”) are the worst. Rubbery, gelatinous, otherwise texture-less, with the flavor of raisin-y burnt bitter sugar and little else. Similarly, cheap wine is often sweetened to cater to Coca Cola-swilling palates.

Low cost, big brand wines have a shocking amount of residual sugar left in them to make them pleasing to people who don’t really like wine. The wines are low acid, simple in flavor profile, often over-oaked using oak chips so that there’s nothing counter-balancing the total cloying richness. What you end up with is a wine that’s akin to a cheap fruitcake: thick, cooked fruit-y, with burnt/charred or butter-bomb flavors filling in the gaps. It’s Cola, but wine.

If you like that sort of thing, awesome, you’re a beautifully cheap date; but if you don’t, that doesn’t mean you don’t like sweet wines. It just means you dislike sweetness when it’s covering up for “meh”-ness.

The British even call dessert wines “pudding wines” - literally the fruitcake of wines! And dessert wines tend to be as indestructible and incomprehensibly age-worthy like my mother’s fruitcake proved to be, thanks to the hefty amounts of sugar accompanied by alcohol (aka fortification, the addition of high-proof spirits to a wine), and even purposeful oxidation and/or heating of the wine. Because when a wine is already oxidized or cooked, there isn’t much else that can be done to it.

Returning to the subject of sweetness: even wines that are only “Off Dry” or Semi-Sweet, like Riesling, Gewurtztraminer, Muscat, or sweet sparkling wines like Moscato D’Asti - the bulk exports of these also use sweetness to make meh-level juice taste okay. But good rule of thumb: if someone has an off dry or semi-sweet white wine and the cost isn’t stupid levels of affordable? You may be surprised how good it is.

Speaking for myself, up until recently - even though I was loving sweet dessert wines I still found myself turning up my nose at Moscato D’Asti (a medium-sweet sparkling wine.) But then someone poured me a $20 bottle of the stuff, which is obscenely high price for a D’Asti. And folks, it was SO TASTY, and not at all cloying. I could drink the whole bottle without tiring of it.

It was unquestionably at a level of sweetness that was comparable to other Moscato D’Astis. Yet nevertheless on another level of enjoyment.

So what was the difference?

It’s All About Balance

In most cases, Acidity is the counter-balance to sweetness, especially when talking about literal sugar-sweetness.

Think about how much sugar you can dump into lemon juice just to make it bearable, just to make it drinkable. If you took that same amount of sugar and dumped it into something pH-neutral - like water - it’d suddenly be undrinkable. Because acidity blankets our perception of sweetness. To where you need to pump acidic juice full of so much more sugar just for it to punch through.

So if you make this rich, syrupy, decadent sweet wine, you generally need high levels of acidity to make it truly porch-poundable. If you’re going to make a Riesling or Gewurtztraminer even so much as “Off Dry” or Semi-Sweet, it can’t be poor quality fruit which usually = overripe and so lower acid which creates a “flabby” final wine. It’s like flat Coca-Cola. It nasty.

Some of the most coveted sweet wines of the world use infamously high-acid grapes, such as Furmint for Hungary’s Tokaj Aszu or Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc for France’s Sauternes. Even Grenache (a high acid red grape) for Vin doux Naturels from Banyuls, Maury, and Rivesaltes.

Haven’t heard of most of these? Or any of ‘em?

Neither had fellow FilmStack Substacker Avi Setton. And he was just as sus as the rest of you. But over the last month and change he was willing to be a test subject for me, and purchased a number of dessert wines he likely never would have considered if I didn’t push hard for them.

And folks, Avi is now on a sweet wine JOURNEY that may never end! (Just ask him!)

Let’s briefly go over some of the best of the most prevalent that are out there. Because there’s no better time for decadence and sweetness than the holidays and the colder winter months! And while maybe SOME small fraction of you truly can’t stand sweetness in any wine, I’m willing to bet that most of you will be shocked to try a sweet wine made from top quality grapes and crafted in a time-tested fashion.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of dessert wines - nearly every country if not every wine region has their own traditional dessert style. But here’s a list to get you started and then some.

Note that many of these wines come in “dry” or unsweet styles as well, but I’m only here to cover the SWEET stuff.

FORTIFIED WINES

1. PORT (Ruby, Tawny, White, LBV, Vintage)

Possibly the most internationally renowned of all dessert wines, Port wasn’t created by the British, but they essentially strongarmed the category into being an international export before it was a classified style or region.

When young wine merchants went to Portugal to gain experience, they tasted a sweet, smooth, fortified wine and were so impressed they sent it back home, knowing it would survive the journey thanks to the fortification and sweetness. And from there, let’s just say it became “a thing”.

Port is still made by traditional foot-stomping of the grapes, followed by a short fermentation process which is halted by the addition of high-proof brandy, leaving behind plenty of sweetness but also additional alcohol thanks to the brandy. And brandy, it should be noted, is made by distilling wine. So it’s all still wine, all the way down!

The British created and/or bought the major Port houses over time, so most big brand Ports out there are British owned and operated, even though the wine has to come from and be made in Portugal. New Port brands owned by the Portuguese have sprung into being in recent years - and if you can find these smaller brands, the Ports tend to be less sweet, more restrained, with greater emphasis on textures and (for lack of a better term) wine-y flavors rather than Port-y flavors.

There are two major styles of Port - RUBY and TAWNY.

a) RUBY PORT is younger Port, of mixed vintages to make the most harmonious blend so it’s ready for drinking right away. Aged in larger oak barrels so there’s less wine touching the oak, exposing it to less oxygen and less oak influence. Ruby Port tends to be fruitier, jammier, with more grit in its texture.

i) LBV or Late Bottle Vintage Port is Ruby but of a single dated Vintage (so there will be a year on the bottle. It’s held back until it’s ready to drink right away, and hence the “Late Bottled” designation.

ii) VINTAGE Port is a Ruby of a single vintage but using only the finest of that year’s harvest. There’s a catch, though: it isn’t held until it’s ready, so while a Vintage Port will be the most expensive and of the “highest quality”, it generally won’t be at it’s peak until 10 years after it’s dated vintage. So if you buy a 2019 Vintage Port, try to hold off drinking it until 2029. You can, of course, try to het an already aged Vintage Port, but boy oh boy is that gonna cost ya.

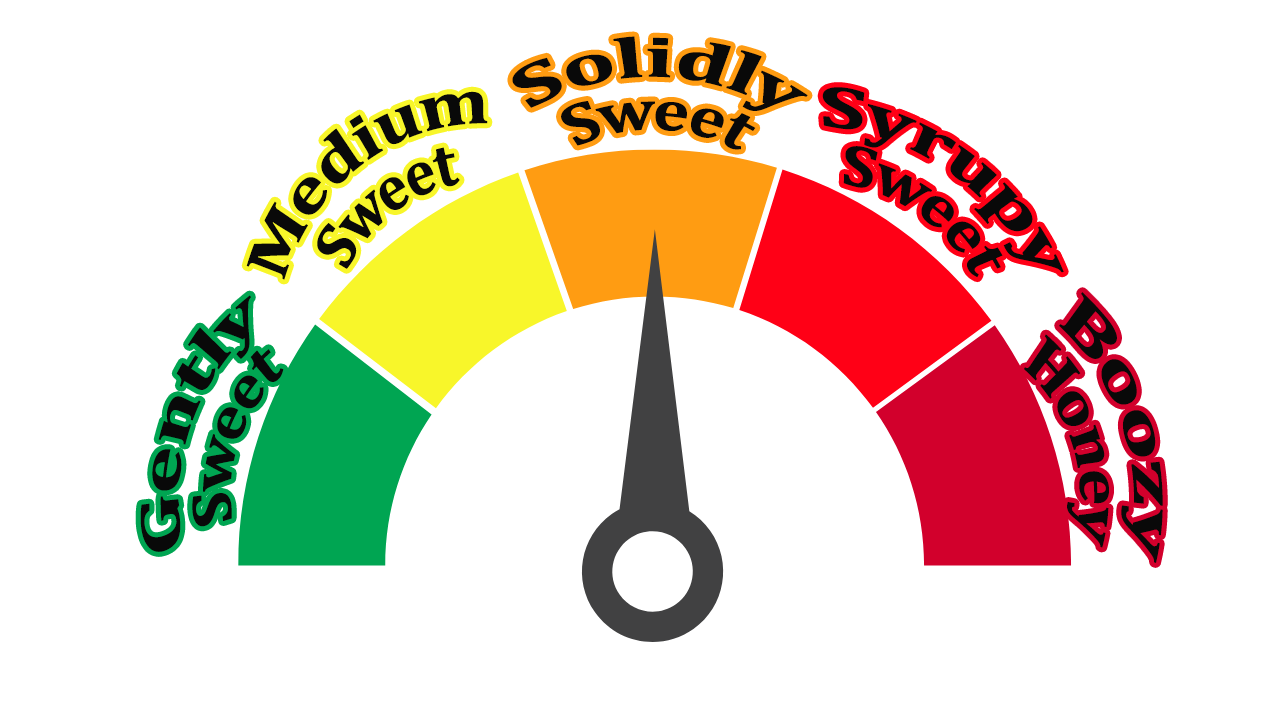

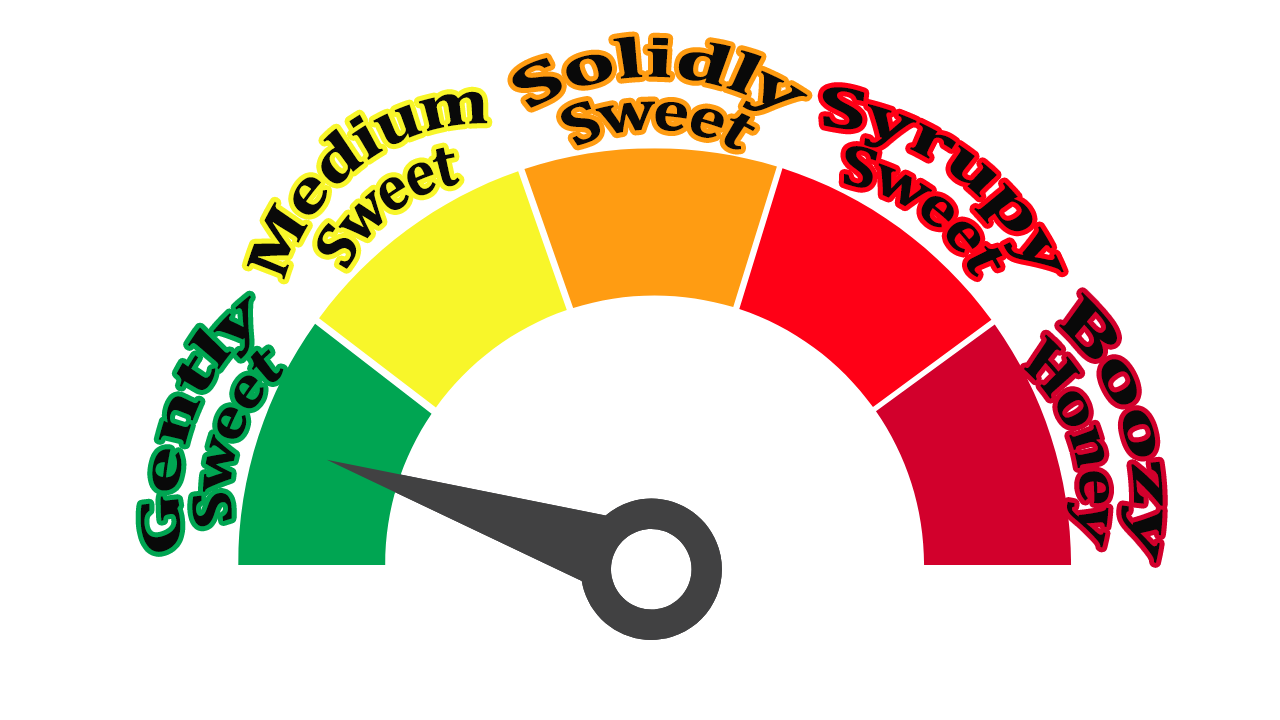

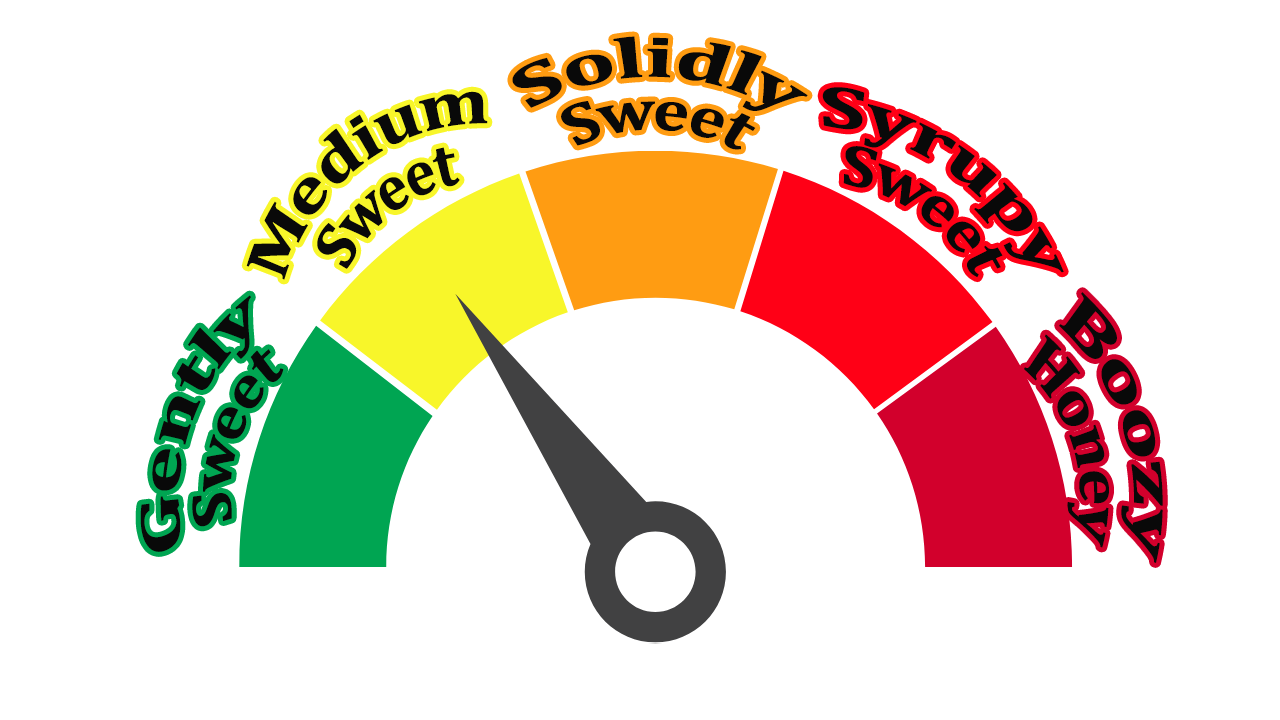

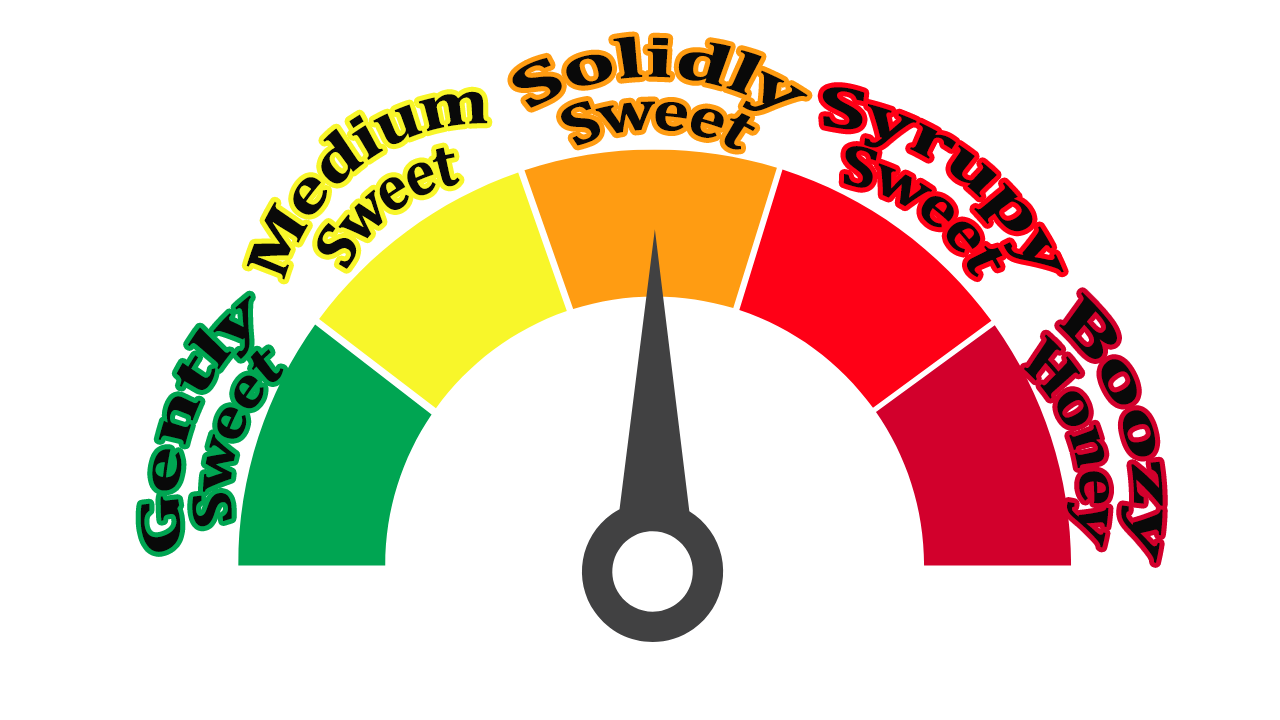

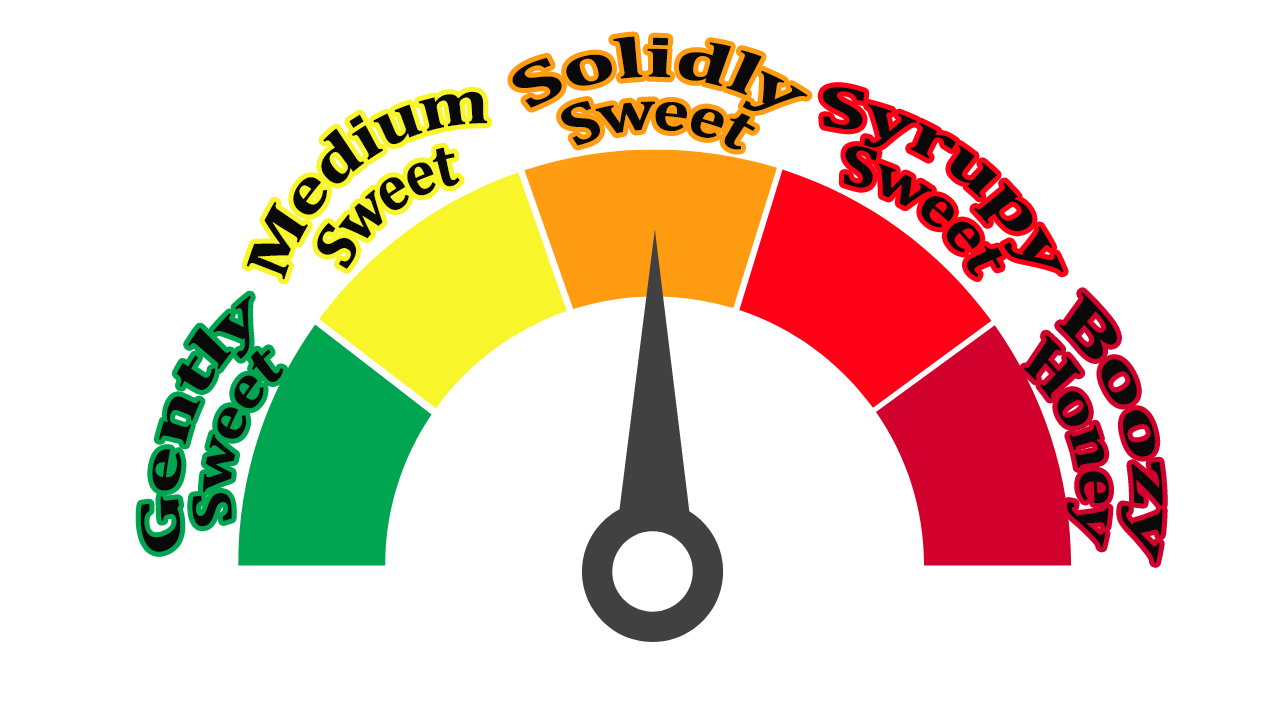

RUBY PORT SWEETNESS:

b) TAWNY PORT

Tawny Port is made in smaller oak barrels, typically over longer periods of time, so the wine soaks up more oak influence and oxidizes slowly but more emphatically, leaving behind a “tawny” (brown) colored liquid with flavors of caramel, brown sugar, maple syrup, nutty notes, and brown fruit like figs. Tends to come in 10, 20, 30, and 40 Year designations, telling you how long they aged it in barrels before bottling.

You can find even younger Tawny Ports (usually called “Fine Tawny” or simply have no number of years designation on the bottle) but you’ll notice those “Tawny” wines have barely turned brown, still looking, smelling, and tasting more like Ruby than Tawny. Though sensitive palates will still pick up some flavor and aromatic differences.

There is no designated differences in terms of sweetness between Tawny and Ruby Ports.

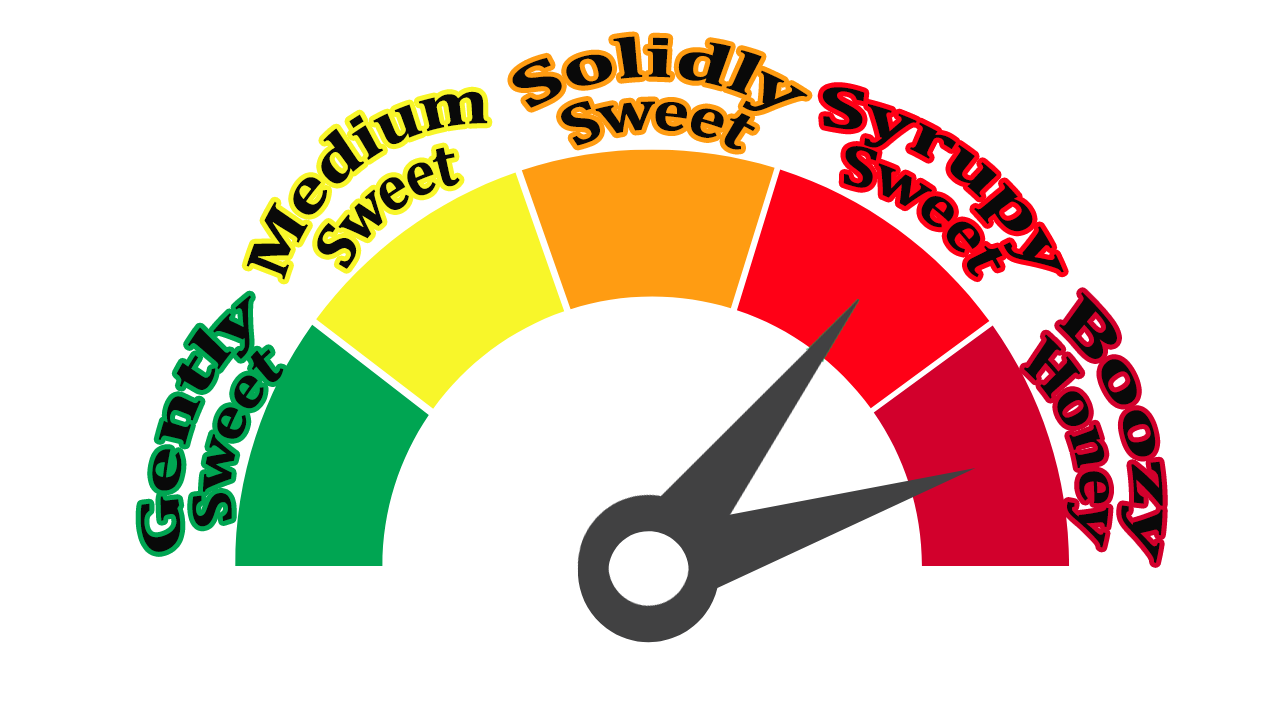

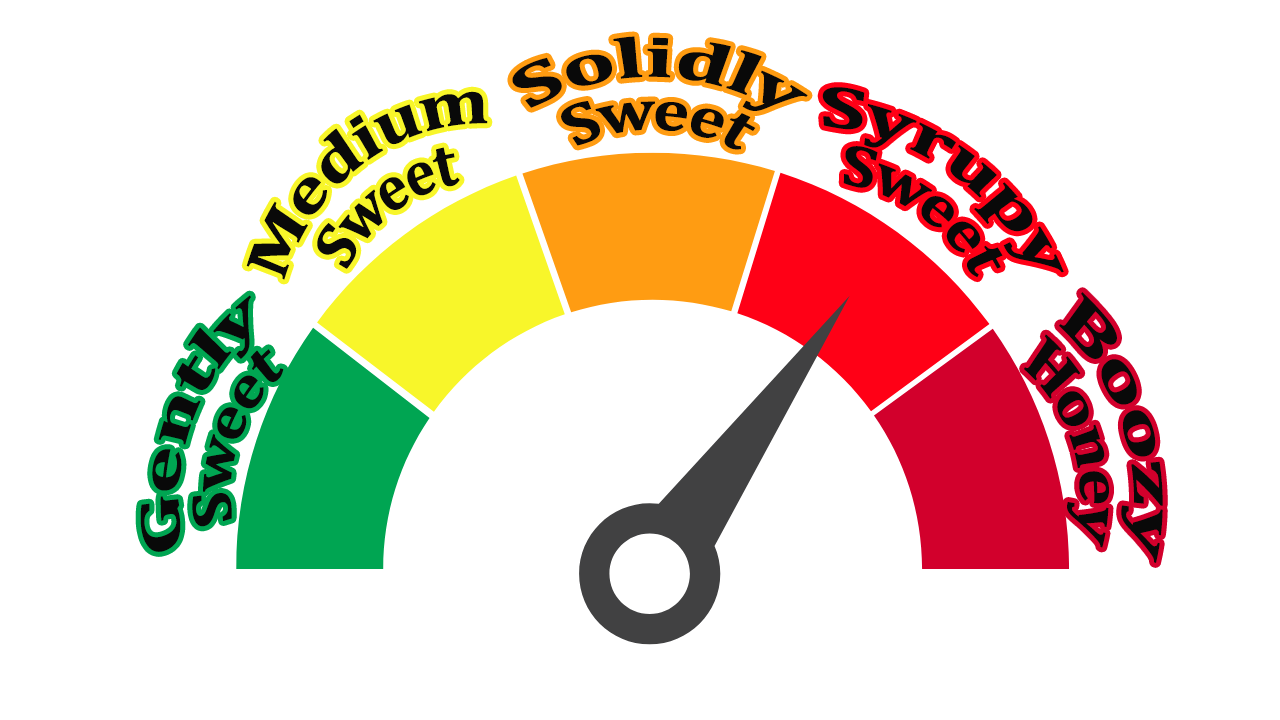

TAWNY PORT SWEETNESS:

c) WHITE AND ROSE PORTS

They also make White (no grape skin soakage) and Rose (minimal grape skin soakage) Ports, and these are often less sweet than their Red and Brown counterparts. Still plainly sweet in style, they can also taste more boozy, as there’s less overall flavors getting in the way between your tastebuds and the BOOZE.

That said, the total experience is more subtle, less powerful aka punch you in the mouth-ful. They even make White TAWNY Ports if you want some maple/caramel flavors in your dessert wine! White Tawny is THE BOMB, people.

I’ve actually never yet stumbled onto a Rose Port, but I hope to someday.

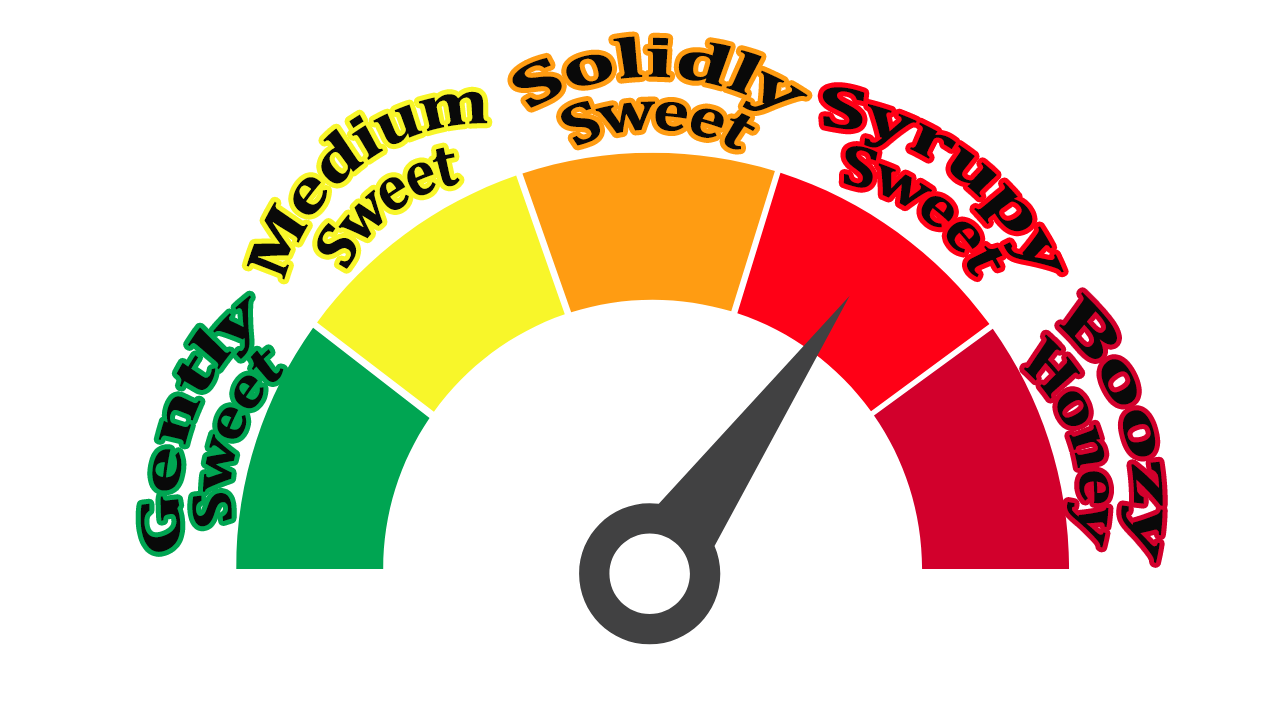

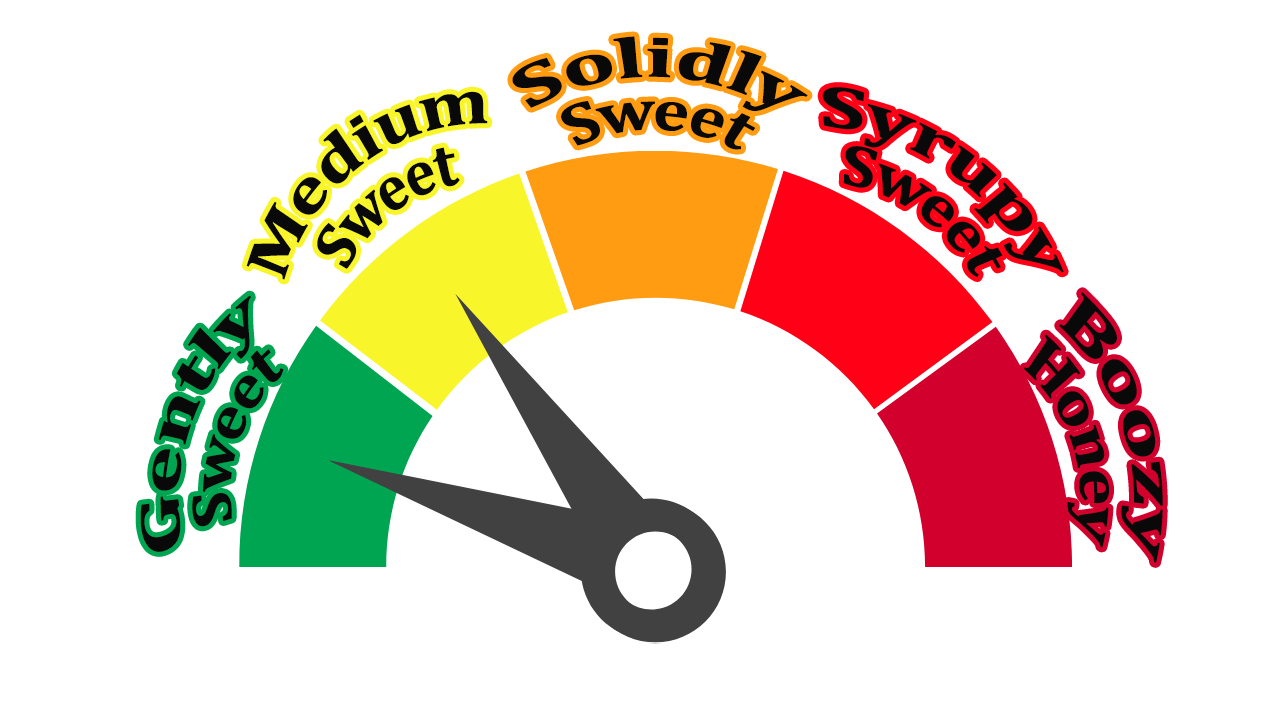

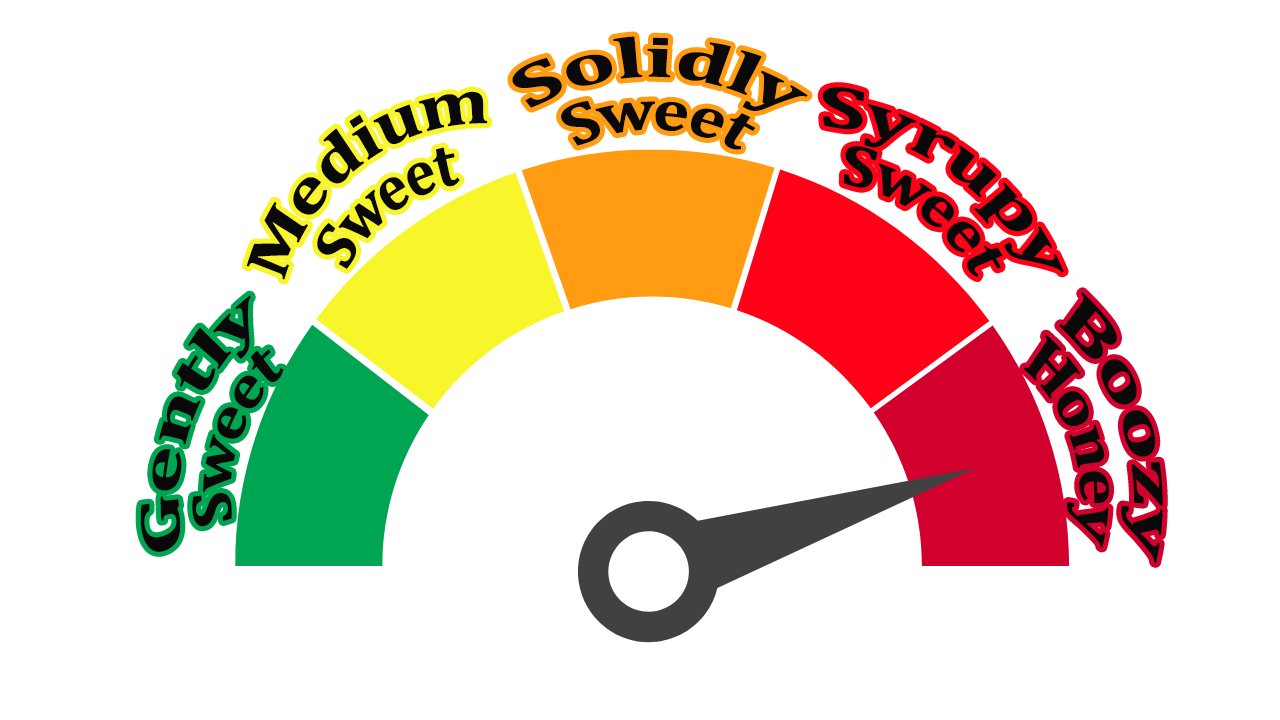

WHITE AND ROSE PORT SWEETNESS:

2. Madeira (Bual, Malmsey)

The sister sweet wine to Port, hailing from the island called Madeira which is considered part of Portugal. The island used to be a significant port for trade ships, and the wine was made by happy accident: they’d fortify wines to help them preserve over the long journey overseas (much like they fortified Port) but then as the ships sailed through the tropics, the wine would heat up and cook every day, while cooling at night, then cooking again during the day, etc.

By the time the wine arrived to its destination, what was left was a sweet, fortified, slowly cooked wine, and it was BETTER THAN THE INITIAL WINE.

These days, they leave Madeira out in the sun to bake multiple times, in waves, over time (though some cheaper Madeira is cooked this way in heated tanks.) It comes in dry to medium sweet to ultra-sweet styles. And trust me: it’s the dry style that will challenge you the most. I would stick to medium to super-sweet, which are both tremendous.

One of the neatest aspects of Madeira is how they use different grapes for different sweetness levels: it’s not all the same wine with different levels of sugar, they tailor the grapes to match what they’re trying to make!

Madeira also comes in multiple “quality” rankings - Rainwater, Finest, Reserve, Special Reserve, and Extra Reserve. These generally have to do with how long the wine was aged, and while “Rainwater” used to be only good for cooking vs. drinking, there are today a number of Rainwater and Finest that are wonderful to drink straight. If you’re paying less than $15 for a full bottle, okay just cook with it. But more than $15? Try a sip first.

a) VERDELHO

Medium dry (aka gently sweet or even a little less). Made with the Verdelho grape, this is a version to definitely serve chilled, with flavors of raw nuts, citrus, and straw/hay.

b) BUAL (or BOAL)

This is the medium sweet style, a blend of dry and sweet batches made with the Bual grape. It was made once again for the British palates and it is wonderful. Not too much, with plenty of vanilla bean and cinnamon graham like flavors.

c) MALMSEY

This is the real deal, the super-sweet stuff made with the Malmsey grape (yes, they name each style after the grape used.) Burnt caramel and soy sauce and sweet like a well-torched creme brulee. Just luscious.

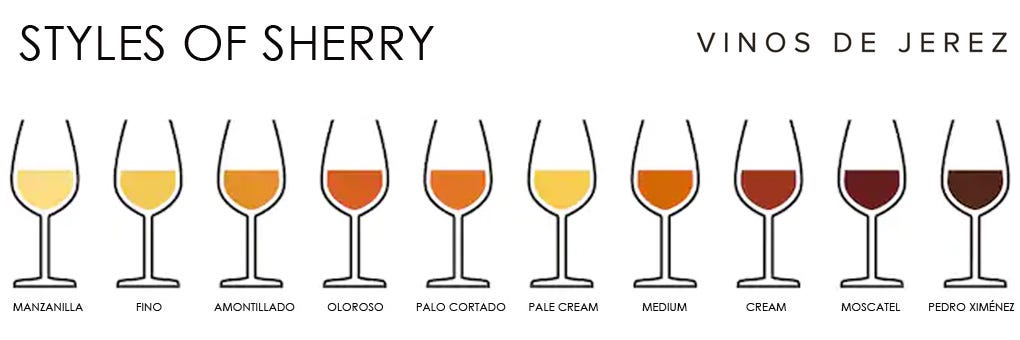

3. Sherry (Cream, Pedro Ximenez)

Trying to explain how Spanish Sherry is made is one of the (if not THE) most complicated and convoluted things to attempt within the subject of wine. Trying to wrap your head around it probably *will* bring you to hate sweet wines.

So I’m not going to go deep into it, but here are broad strokes. Note this is all a gross oversimplification but it should still all be accurate and operate as a beginner’s primer:

All Sherry is made via a “Solera” method, which is a blending of older and younger vintages, that continues indefinitely. Every year new young stuff is added while some of the oldest part of the Solera is siphoned into bottled for that year’s release. Most of the oldest is always left behind while the younger bits are added to top it off. There are usually 4 tiers of aging, with the youngest topping off the second youngest and then that topping off the third youngest and so on into the oldest. Many Solera systems have been ongoing since the early 1900’s or even the 1800’s!

Sherry comes in multiple dry and sweet styles, some oxidative (purposefully exposed to oxygen) and some non-oxidative.

All Sherry is fortified with Brandy, like Port.

All Sherry is aged in open top barrels (hence the oxygen.)

However, for some Sherry they allow the dead yeast after fermentation to form an air-tight seal on the top - which they call the “flor”. (Hence the option of non-oxidative.)

Dry and non-oxidative Sherries are aged in this way, steeping in the barrel and on the flor without air getting to the wine, thus creating a nutty, salty, dry and fortified white wine with zero sweetness - these are the “Fino” and “Manzanilla” categories of Sherry.

Then there are the dry Sherries exposed to oxygen, to turn brown and caramelly - the Dry versions of this are the Amontillado and Oloroso categories.

“Palo Cortado” is a category that blends the dry oxidative and the dry non-oxidative styles into one.

And then we get to the sweet Sherries: Cream and Pedro Ximenez (or “PX”).

a) CREAM SHERRY

Invented for the British palate (sense a trend here?) and blends half dry Sherry with half Pedro Ximenez sweet Sherry, making for a medium-sweet dessert wine. It’s often looked down upon by wine snobs (and especially Spanish traditionalists) but holy cow, it’s the PERFECT level of sweetness!

Technically Cream Sherry comes in 3 different levels of sweetness: Pale Cream, Medium, and Cream, depending on how much of the sweet Pedro Ximenez they blend in. I’ve only had the stright-up Cream version, which is sweet like so:

I imagine the “Medium” is Medium Sweet, and the “Pale Cream” is Gently Sweet, but since I can’t say for sure, I won’t post a sweetness graph for them.

b) PEDRO XIMENEZ

This stuff is like syrup in a glass. It is SWEET, but gorgeously so. It’s dark and brooding with notes of burnt brown sugar, caramel, mahogany, tobacco, brown fruits, and brown butter. Buy a half-bottle and seriously treat yourself.

4. Vin doux Naturel (VDN)

The great sweet wine of Roussillon, in Southern France. These are wines fundamentally made via fortification / “mutage” - the addition of high alcohol (190 proof!) spirits like Brandy to halt fermentation, and leave behind lots of sugar from the original grape juice and also high alcohol thanks to the spirits.

(You’ve probably noticed that this “mutage” is a key step in many dessert wines in this article. Though this isn’t the only way to keep sugar in wine - the very next entry after this will reveal a different way!)

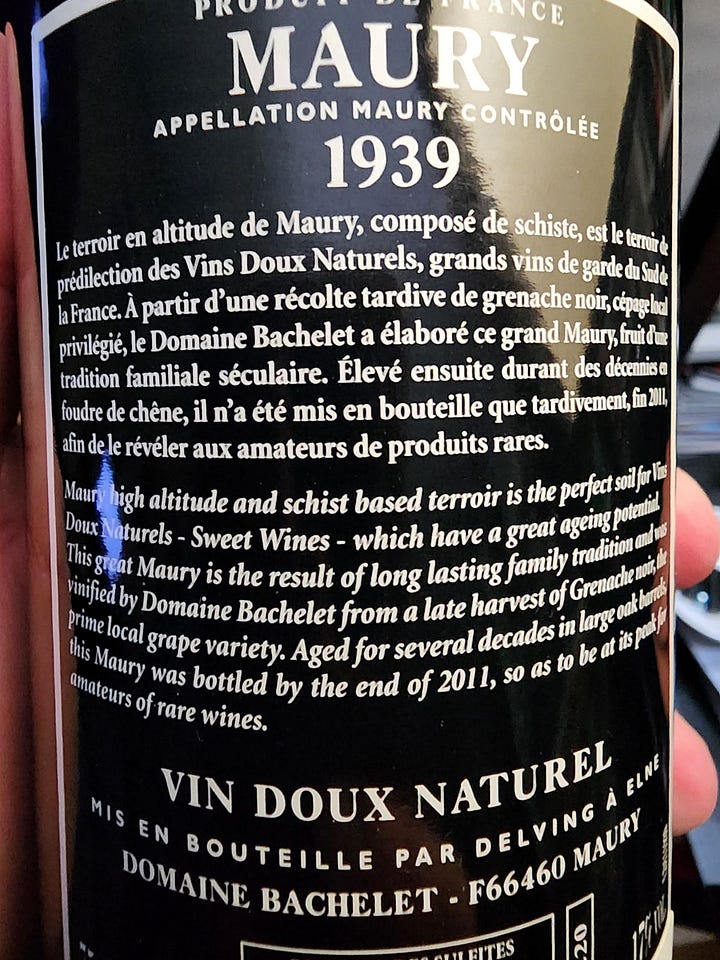

But first: Vin doux Naturels. Made in both red and white, with Grenache as the primary grape in the reds and two different Muscat grapes for the whites. Grenache (also known as Garnacha) is a high-acid red grape, which helps counter balance the sweetness of the doux Naturels. I’ve never had the whites, but hope to someday soon. For now, let’s look at the reds.

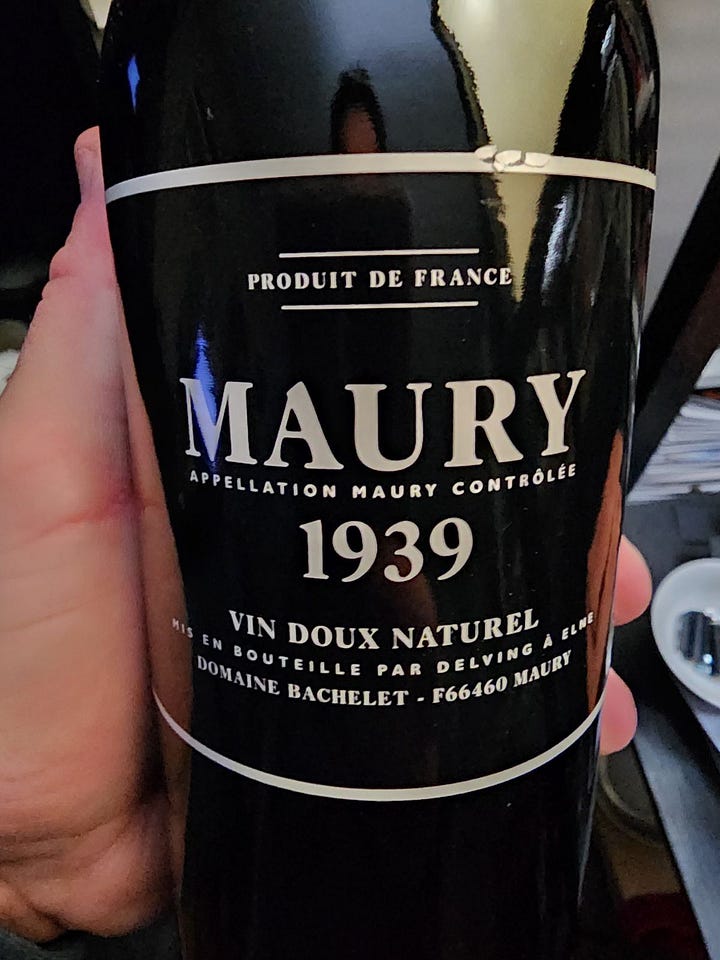

The best Vin doux Naturels are considered to come from Maury, Banyuls, and Rivesaltes, so look for those 3 terms on the bottle. The wine is fortified and then aged in large oak barrels for DECADES before bottling. I have a 1939 (!) Maury that wasn’t bottled until...2011. Yup, the fruit was picked before America joined the Second World War, then was aged for SEVENTY TWO YEARS before bottling! And has now sat in bottle for an additional 14 years.

Vin doux Naturels can come in both oxidative and fresher, fruitier versions. The older the wine, the more likely it’s oxidative as that helps the wine age longer without fault. Fruitier styles will be made for drinking “sooner”, though even these will be decades old. The current “fruitier” releases I’ve found in my local shops are from 1970-1985.

So if you want a taste of real history, seek out a VDN. They’re not too ridiculously sweet, and are just about bursting with layers of flavor.

5. Vermouth

One of my absolute favorites. Named after its main ingredient, Wormwood (which the Germans pronounce “Verm-vut”) Vermouth was originally a medicinal beverage made from Wormwood + a litany of additional botanicals - herbs, barks, fruits, and flowers - each maker having their own proprietary blend. Germany is where it began, with France, Italy, and Spain also having their own time-tested, traditional styles to offer.

In Vermouth, it’s not just acidity but the bitterness of the botanicals that counter-balances the sweetness, making for a gloriously bittersweet experience. Dark chocolate lovers should apply.

Most people think of Vermouth only when they think of Martinis - but you use the dry version of Vermouth for that cocktail (and fyi, Vermouth IS in fact wine, so don’t leave it unrefrigerated after you open it! It goes bad fast like wine does!) The sweet version of Vermouth, on the other hand, is meant to be sipped neat and chilled, even over a little ice is nice, just find your preferred method.

Vermouth is made from an “aromatized” (steeped in botanicals) base wine which is then fortified. It comes in all the color styles - Red, White, Rose, and Amber/Orange.

So which Vermouths should you drink straight? Good rule of thumb: of you’re spending $15-30 on a half bottle, or $20 - $40 on a full bottle, you’re probably in the right ballpark. Vermouths meant only for cocktails and cooking tend to be $5-$15 for a full bottle.

Valdespino Vermouth from Spain is one of my all-time favorites (~$30 for a bottle), as is Carpano Antica from Italy (~$20-$25 pr half bottle.)

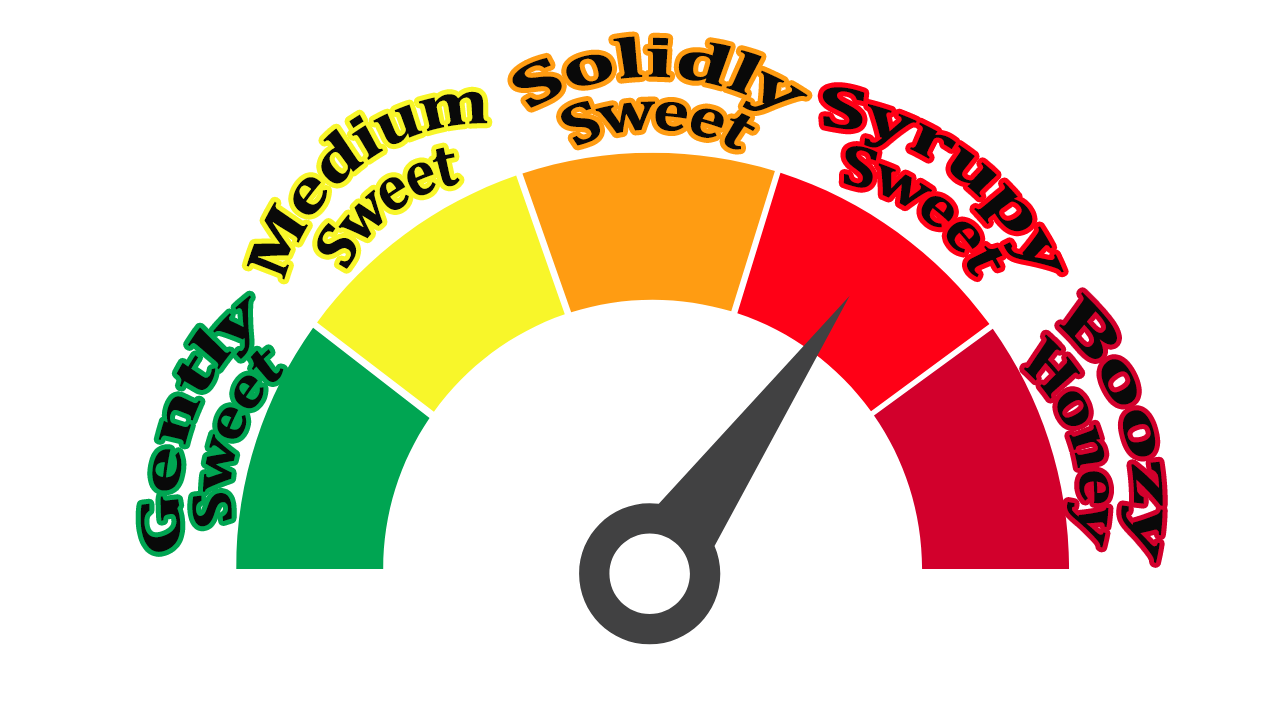

VERMOUTH SWEETNESS:

BOTRYTIZED WINES

1. SAUTERNES

The most internationally renowned dessert wine of France, hailing from he Sauternes region which predominantly makes this sweet wine from Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc. (The best are Semillon-heavy.)

These are both high-acid white grapes that are allowed to hang on the vine until a very specific fungus takes hold: Botrytis aka “noble rot”.

Botrytis pokes little holes through the grape skins to get to the juice inside, and by doing so dehydrates the grapes, partially “raisining” them. When just the right amount of Botrytis has infected the crop, and the grapes are just the right amount of raisined, the grapes are picked and crushed and fermented.

The dehydration concentrates the sugars so much that fermentation naturally stops (the yeast having all gorged themselves to literal death) with a hefty amount of sugar STILL left behind! Plus, the Botrytis fungus itself is allowed to remain in the juice during fermentation, as it lends surprisingly pleasant honeyed, caramelly, dried fruit notes which are all enhanced by additional aging in oak.

Sauternes’ high acid, seeming lightness on a palate, moderate alcohol (13-15%, on average), and while it contains high levels of residual sugar, it’s high high acidity has made it one of the most easy-to-love sweet wines in the world. If you’re truly unsure how sweet you want to go, start with a Sauternes.

SAUTERNES SWEETNESS:

2. Tokaj (Late Harvest, Aszu, and Eszencia)

On the other side of Botrytized wines, we come to Hungary and it’s blisteringly acidic grape, Furmint.

With such a grape, the Hungarians allow Botrytis to overtake it, and then do something utterly unique in he world of sweet wines: they hand pick only the most perfect botrytized grapes (which they call “Aszu berries”), tossing the rest, then soak those in a base of dry wine for 24-48 hours before being pressed. This very sweet juice would then age in Hungarian oak in cool but humid conditions for years. This creates wines of deep amber color, caramelized flavors, and nutty, complex aromas, balanced by Furmint’s naturally high acidity.

The total number of Aszu berries added to the base wine increases the total final sweetness. They call each barrel of Aszu berries a “puttonyo”, so you can find Tokaj Aszu in levels of 3, 4, 5, or even 6 Puttonyos, telling you the total level of sweetness. The more hand-picked Aszu berries used, the more expensive the wine, as it requires a lot more labor and a lot more discarded grapes!

In recent years, the “Aszu” style is now only for 5 and 6 Puttonyos, with subtler levels of 3 and 4 Puttonyos now being called “Late Harvest” Tokaj.

a) LATE HARVEST (3 and 4 PUTTONYOS)

b) ASZU 5 PUTTONYOS

c) ASZU 6 PUTTONYOS

d) TOKAJ ESZENCIA

That brings us to Eszencia aka “Essence”, the sweetest of the Tokaj (”toh-kai”). Made from only the free run juice (without pressing) of the Aszu berries, it is crazy sweet at roughly 450g of sugar per liter. To put that into context, dry wines are <1g of sugar per liter! Eszencia is more like nectar than wine - it’s drinkable honey, made to be supped in very small 1oz pours at a time. Though thanks to Furmint’s acidity, it still shockingly balanced. And highly recommend. It’s pricey, but you’ll drink it very slow, and it will last / can age a very long time.

ESCENZIA SWEETNESS:

Ice Wine (Eiswein)

As a Michigander by birth, this one is near and dear to my heart.

Ice Wine can only truly be made where it gets cold enough to freeze the grapes while still on the vine. (Though you can find much more affordable version of Ice Wine where they freeze the grapes artificially after harvest.)

They then crush the grapes while still frozen, which keeps all the water out of it, and the not-quite-frozen sugars then slowly drip out. It can take hours after pressing for the first drops to finally fall. And by the end, this method only collects about 20% of total volume you’d get from unfrozen grapes.

As such, Ice Wine can be expensive, as you’re sacrificing 80% of the usual volume to make this intensely sweet wine. The 20% collected has so much sugar, the yeast dies by engorgement, leaving behind highish levels of alcohol but also very high levels of remaining, residual sugar.

In Germany, where the style was invented, Eiswein is the second-most sweet version of wine they make (with the most-sweet being a Botrytized [see above] wine!)

Ice wine is usually made with high acid grapes like Riesling, Vidal Blanc, and Cabernet France (for a red version) to balance out the sweetness. Ice Wine isn’t quite to the level of sweetness as a Tokaj Escenzia (really, nothing is) but they are still typically twice as sweet as Coca Cola.

ICE WINE SWEETNESS:

Not The End

Whew! And this is just a smattering of what’s out there! I may have to do a Part 2 some day. There’s still Late Harvest wines around the world, Recioto and Chinato from Italy, Vin Santo from Tuscany and Vinsanto from Santorini in Greece because that’s not confusing at all, Straw Wine from the Jura in France, Angelica from the Americas, the list goes on and on.

If you haven’t treated yourself to a carefully crafted, beautifully made dessert wine, you owe your palate the chance to truly weigh in. More of you like this stuff than you think. More of you LOVE this loveliness than you think.

Let your preconceptions go. Let the shitty wine, sweetened to cater to your Coke-swilling palate, go. And dive into the near-endless world of sublimely sacchrinous satisfaction.

Chin chin.