Wine Conversations: Grappling with Authenticity (IV) - There's (Almost) No Such Thing

Can something like "Authenticity" be determined outside of personal preferences?

Make sure you read the previous 3 installments of this Wine Conversation between mutilple wine writers across WineStack.

George Nordahl kicked it off by discussing how little it actually takes to be literally authentic - commuicate the truth of what’s in the bottle. Then the role that privilege plays in weaponizing the term otherwise, and how little the term truly means within these contexts.

Aleksandar Draganic expanded upon this by documenting the massive changes within the wine industry in recent decades, the sheer variety of wine and styles now available and the democratization of what is considered “authentic”, and once again how little meaning the term weilds within these considerations.

Maria Banson made a brilliant comparison to the ultra-traditional art of Opera, and how the introduction of HD cameras prodded traditionalists to cry “inauthentic!” and yet audiences loved it, and now it’s a staple of the art.

The core point being: THINGS CHANGE. Change doesn’t obliterate history, nor does it transform an art into something “inauthentic” or unrecognizable. It’s just a change. It’s just evolution. Which, as actual wisepeople know, is the only constant. If change made things inauthentic, we haven’t lived in an authentic world since Existence, Day 2.

Histrionically Speaking

Ahem, historically speaking, when it comes to wine, the term "Authenticity" is a sister to "Typicity", and both are relatively new.

Felicity Carter and Pauline Vicard spoke at length about the history of these two terms - I highly recommend you give it a listen!

“Authenticity” was a concept that began in the wake of the phylloxera epidemic in Europe, and the rise of fraudulent bottlings because France lacked the grapes necessary to meet global demand. But it wasn’t just the fraud abroad - initially the French countered by instigating a rule that wines "from a place" would receive a premium in terms of price. But this led to over-planting, high yields, the wines were from where they said they were from, but there was no regard for quality.

So then the AOC system was born in 1935 as the counter to the counter, to correct the mistake of allowing so much low quality wine to be made in premium-priced places. And here is where the term "Authenticity" rears its head.

It of course was as much a branding term (or "marketing" term, as Maria Banson called it) so that buyers could always know precisely what they were getting based on the mark of AOC "authenticity".

"Typicity" is the more recent term, and was fraught with tension right from the offset. I refers to something "...original that stands out, but is recognizable enough that it can serve as an example." It was first used around 1979/80; historically a very new concept, conjured due to the French suddenly being exposed to international competition. (It's no coincidence that their loss to Napa Valley wine at the Judgement of Paris took place just three years prior, in 1976.1) And the push-pull of the term's two criteria - original but also recognizable - has kept it from achieving a global consensus as to what qualifies.

Now with the rise of Natural wine, Organic, Biodynamic, and Regenerative farming practices, new additions have been heaped onto both terms, with every wine drinker seeming to have their own interpretations of where the lines are drawn.

We all believe there ARE lines - a point at which a wine ceases to be "authentic", "typical", or "honest". But can these lines be drawn in any logical way that rises above subjective preference?

Let's Give It a Proper Philosophical Test

No matter how "minimal" the intervention, winemaking will always include active decisions - those grapes aren't going to gather together, crush themselves, or separate themsleves from their own skins, or control the ambient temperature around them during fermentation and aging. Minus using massive amounts of chemicals in the vineyard, the growing of the grapes is rarely where the claims of authenticity live or die.

So let's consider what types of winemaking / vinification decisions might move the needle from authentic to inauthentic:

-There's using commerical vs. wild (native) yeasts - this might make a wine more "local", but does that make a wine less "authentic"? Does a Syrah from Crozes-Hermitage not taste like it's a Syrah from Corzes-Hermitage because commercial yeasts wipe out all trace of terroir and typicity? Is selecting the type and flavor of yeast(s) used any different than selecting the grapes planted, maceration style, or aging containers used? Selection is selection.

No matter how "minimal" the intervention, winemaking will always include active decisions - those grapes aren't going to gather together, crush themselves, or separate themsleves from their own skins, or control the ambient temperature around them during fermentation and aging. Minus using massive amounts of chemicals in the vineyard, the growing of the grapes is rarely where the claims of authenticity live or die. So let's consider what types of winemaking / vinification decisions might move the needle from authentic to inauthentic.

-There's using commerical vs. wild (native) yeasts - this might make a wine more "local", but does that make a wine less "authentic"? Does a Syrah from Crozes-Hermitage not taste like it's a Syrah from Corzes-Hermitage because commercial yeasts wipe out all trace of terroir and typicity? Is selecting the type and flavor of yeast(s) used any different than selecting the grapes planted, maceration style, or aging containers used? Selection is selection.

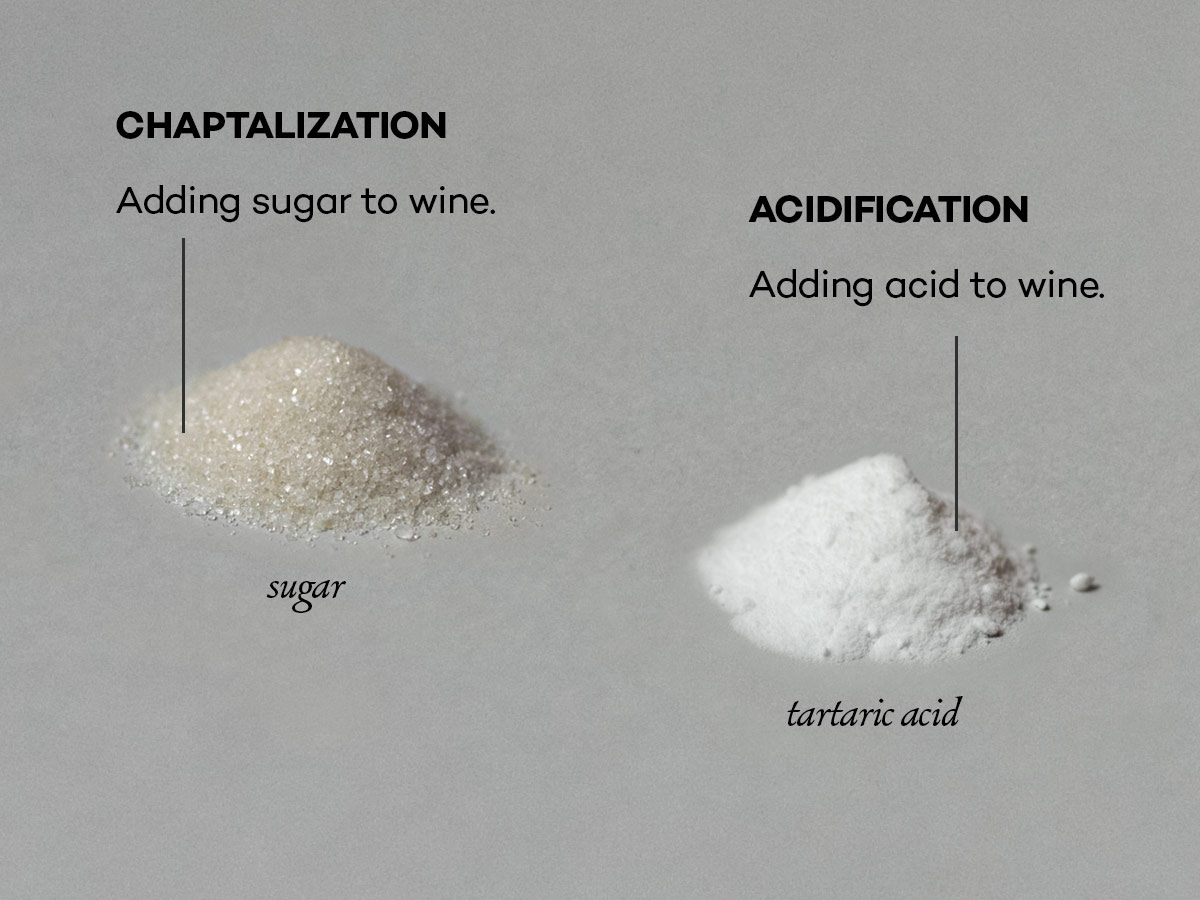

-There's chapitalization (adding sugar to create more alcohol in originally underripe fruit) though this is a process accepted in Champagne and many German and Austrian wines of high pedigree. You're picking grapes for a certain flavor profile, then tweaking the process to balance the final product. It's "manipulation", but how can it be authentic for one wine and not another? (adding sugar to create more alcohol in originally underripe fruit) though this is a process accepted in Champagne and many German and Austrian wines of high pedigree. You're picking grapes for a certain flavor profile, then tweaking the process to balance the final product. It's "manipulation", but how can it be authentic for one wine and not another?

-There's acidification - adding acidity to low acid wines that need it for balance. Unideal, certainly, but we also allow malolactic fermentation - the choice to allow or halt the switch from sharp malic to softer lactic acid. This is also a manipulation of the final wine's acidity profile. If one does not make a wine inauthentic, why the other?

-There's leaving residual sugar in the final wine by halting fermentation early, but there is nothing objectively superior to "dry" wine vs. off-dry or medium-dry. Pre-1970's many fine wines included small levels of residual sugar. The trend toward fully "dry" fine wine is a recent thing, and while sugar is unquestionably used to cover us flaws in low quality juice, the sugar itself isn't what makes a wine inauthentic. It isn't what makes the juice poor quality in the first place, either.

And good god, what of botrytized wines where a mold is purposefully allowed into the final flavor profile? Ice wines were the grapes are left to freeze on the vine to extract maximal sugar and minimal water? These are heavily manipulated products, but considered “authentic”, for their styles.

-There’s filtration, clarification, and stabilization, using plant or animal products to remove sediment (particles and cloudiness) in a wine, and ensuring byproducts like tartaric acid crystals won’t form if the when gets refrigerated. These are all naturally occuring pieces of a final wine, but is it less authentic to remove them? Is “authenticity” about maximalizing the naturally occuring flavors and aromas that are possible?

-There's oak chips, staves, and other added flavorings - but what of Amaro, Vermouth, dessert wines that are traditionally steeped in dozens of botanicals? What of the difference in aging in New Oak (lots of flavor) vs. Old Oak (almost none?) Where then is the line drawn between “enough” oak influence on the final wine and so much that it is no longer "authentic"?

And then what of secondary fermentation in bottle vs. tank method of carbonization (adding carbonation directly like a soda) for sparkling wines? What of freezing the grape juice until it's wanted to make more wine like in Mascato D'Asti?

The. List. Goes. On.

Conclusion

Show me the method, the thing, the decision, and I'll show you a number of wines where the practice is accepted as part of an "Authentic" process. Why should it be okay for X but not for Y? Or I'll show you how arbitrary aka subjective a drawn line is in terms of why there, and not over here? (Oak chips vs. New Oak vs. steeped in bark and botanicals.)

Now, there is logically some level of extreme where a line will finally be crossed in no uncertain terms, where a wine ceases to be a wine, or anything resembling the many, many, many accepted styles of wine. But anything short of this extreme?

Pure, personal preference.

An overly narrow focus on a single example you're not a fan of while ignoring all contexts where you are (or might be.) There is (almost) no such thing as "Authenticity" in wine. None that can be successfully argued outside of this personal preferenence

Naturally, we each have our personal lines we don't like to cross, for whatever our reasons. At any given point in time, a number of winemaking practices can be heavily associated with low quality bulk / high yeild wine. But low quality isn't the same as "not authentic". Just ask the French, who tried that before installing the AOC system to make sure quality was also included.

And that’s all from my brash mouthy-mouth. On to an actual winemaker (!!), Steven Kent Mirassou to bring this conversation to a close next week!

As I detailed in a previous Wine Conversation, California wine had actually trounced French wine almost a century earlier, at the World Fair in Paris in 1888. At that time, the French cried foul at California's use of the terms "Burgundy", "Bordeaux", "Sauternes", and "Rhone". This seems fair from a modern perspective, but it's important to remember that wine outside of France, on the global scale, was entirely new. The French were victim of their own monopoly - people drank "Burgundy" and "Sauternes", not Pinot Noir or Botrytized Savvy B and Semillon. So California used the words people understood. They also clearly stated that the wine was from California.

Nevertheless, after this 1888 loss the French passed a rule disqualifying all wines from future World Fairs that used the names of places they weren't from on the bottle, thus keeping the same losses from happening again (and Prohibition soon came for American wine after that.) Again: this seems fair from a 2025 perspective, but in 1888 this was more like the recent Prosecco / Glera debacle. You allow your countrymen to immigrate and take your vines and knowhow and terminology with them, based on whatever rules (or lack thereof) existed at the time, then pull the rug out from under ONLY when they begin to prove competitive.

https://www.amazon.com/Authenticity-Provocations-Peter-York/dp/1849547874