Why Is It So Hard to Let Go of Franchises?

They're not merely a symptom of IP-worshipping modernity, but rather an ages-old relationship to storytelling that we have to learn to let go of.

The remake. The reimagining. The redo.

The sequel, the threequel, the requel, the prequel.

The spin-off, the one-off - now sound off: we are so sick to death of these things that in 2025/26 it’s a punchline WAIT WAIT WAIT HOLY SHIT THEY’RE MAKING ANOTHER GODZILLA X KONG!!! Um…I mean…

(deep breath) We all want original and unique “content”, or so we say. New stories, new characters, ideally from new voices.

With AVATAR 3: FIRE AND ASH primed to “rescue” the winter box office and Paramount announcing that it’s putting RUSH HOUR 41 into production, the despair feels raw and real.

But this isn’t just late-capitalist malaise. We’re also up against our own gut instincts, our own cultural histories, our own relationship to storytelling and art, and how we engage with it.

Our audience and even ourselves (when we’re the audience) aren’t primed for regular original content, and we never have been. At least not if history is our guide. Let’s take a peek:

Storytelling Has Always Been Reiterative

Starting at the very beginning, when humanity first began telling stories to themsleves, they obviously weren’t written down. They were spread by word of mouth, oral traditions, an ancient version of “telephone” where each storyteller tweaked the tale but it was nevertheless the same handful of tales, re-told over and over and over again. Essentialy, a series of replays and remakes.

Religious texts started this way, copied down on stone tablets or parchment only centuries later, in morphed and tortuously tweaked versions of their original forms. Different cultures had different original stories, but there weren’t that many. Mostly, the stories were re-told, to new generations, to new audiences, just to placate the need to hear an envigorating tale.

As tribes and cultures met each other and clashed, stories merged and transformed and were swaped. But always predominantly (at least to our knowledge) as re-tellings, re-imaginings, and continuations of known and cherished characters.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest preserved stories is actually multiple poems, the total number of authors unknown, all riffing on the same character of Gilgamesh. The poems even span two different cultures within greater Mesapotamia: some from Babylonian peoples, others from Sumerian. Seemingly, “Gilgamesh” was the heroic charcter when you neeeded one, no one bothered to create another. Which points to an interesting default relationship with storytelling: we kept the familiar, the known, the famous main character, then wove new elements around them. Well before copyright law, there was no reason to create new characters “just cuz”.

And the similarities between Gilgamesh and The Hebrew Bible are legion, including the Garden of Eden, Noah’s Flood, even direct lines from certain charcters are easily traced to lines uttered in Gilgamesh. And Homer’s The Iliad is essentially a direct remake, for a then-modern Greek audience.

Staging of Stories

Eventually, live theater came into being. And what does theater do? It stages the same story over and over and over again. A new staging every show. And then a new interpretation with each production/revival.

In Shakespearean times, theater troupes would have, roughly, a month’s worth of plays memorized and rehearsed, and they would stage a different play each night only to restart again the following month. Essentially a TV Guide’s worth of content cycling through its programming.

Certainly, there was original content being made by playwrights and novelists of the time. But not in quantities like we consider them today. Shakespeare himself wrote 38 plays during his lifetime, and even then many were based on the work of other playwrights and recycled older stories and historical material.

The Goddamn Greeks

The outlier to these practices were the Ancient Greeks, who were, as always, obnoxiously ahead of their time.

Plays in Greek culture were performed during the Dionysia festival, so on special dedicated occassions only. But here’s the truly fascinating thing:

The more well-recieved a play was, the more unlikely it would ever be staged again.

Why “remake” something if you got it right the first time? Why chase the lightning-in-a-bottle experience that occured when it’s inevitable that any future attemp will offer diminishing returns?

These are questions we ask ourselves in the 21st Century, but the Greeks felt the same way. And even took it one further: they essentially never wanted to re-experience the same show if it was so good the last time. They treated their plays like TV once treated broadcasts - why would anyone want to watch a broadcast again?!? (“Reruns” were once considered filler that no one got excited about.)

And this brings us to something wonderful in the modern world, that has had the unfortunate side-effect of exacerbating our Franchise mentality:

The Preservation of Culture (While Wonderful) Isn’t Helping

As mentioned, once upon a time TV broadcasts weren’t kept - they were burned. Books, plays, and movies fared a little better - we were only just starting to methodically “preserve” our culture during the 20th Century, and understanding why it was important to do so.

But here’s the thing: look at what happened when Gilgamesh survived: story after story after story became remakes of it.

Name me one decade where a novelist or filmmaker doesn’t try to do a remake of The Iliad or The Odyssey2 or any of the innumerable stories within The Bible. Or of Shakespeare, any 38 of his plays. With these stories preserved, we refuse to let them go, we refuse to not be inspired by them in direct, specific ways.

Considering Live Theater, before we could record them there was never any definitive performance of a show, or even a song. The idea that you could revisit a specific performance of a song or show is historically very new. And “franchises”, as we understand them today, exploded with the advent of first TV, then home video.

Now we re-watch films incessantly. Unlike with Live Theater these rewatches aren’t even new performances, it’s literally the same experience, on repeat, forever, and we pay significant money for this.

We seek out special director’s cuts and “lost” additional materials. We collect them and own whole filmographies, series, genres, and eras. Filmmakers are no longer people fascinated by the craft alone: they’re fans. This is a staus that didn’t fully exist for film until the 60’s/70’s, when generations were able to grow up with film being native to their existence.

As wonderful as it is to have preserved so much of film history, the ability to revisit and revere past works does not help the franchise issue. Once upon a time, a studio might remake a past work for no other reason then they already owned the rights. Now, they have triple the incentive because the IP comes with a bult-in fanbase. Which often includes the filmmakers themselves.

In a World of Over-Abundance, Originality is Suddenly Prized

Editor Girl! (Kris Simon) posted yesterday how the comics industry is entering a similar phase of IP-dependancy that Hollywoood’s been in for the past many years. And she lays out how - while this is “risk-averse” - it isn’t sustainable, and audiiences eventually will look elsewhere.

To quote her:

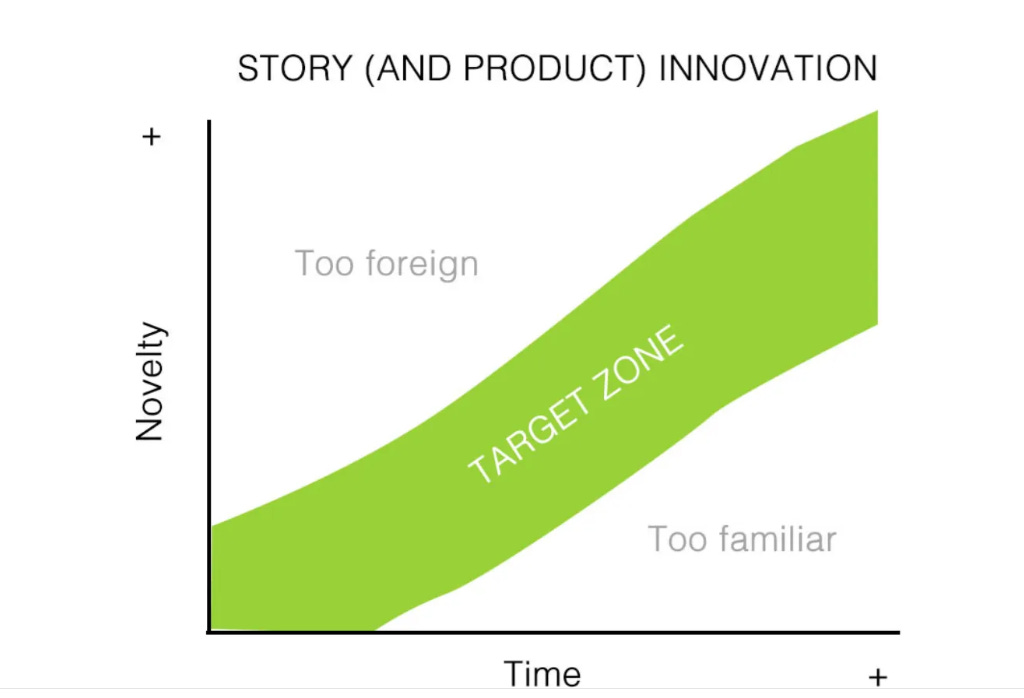

I found this on LinkedIn. It essentially says that audiences crave originality, but not too much, or else they get bored. It’s a fine line, which is why new stories within familiar licensed IPs are a safe bet.

Audiences didn’t stop loving movies — they just stopped showing up for the same movie over and over again. The fatigue set in. The returns softened. The buzz moved elsewhere. Where did it go?

To indie films.

To festivals.

To smaller, stranger projects.

To voices that felt new, specific, and human.

Hollywood didn’t lose its audience; it trained it to look somewhere else.

Comics publishers, especially in the last couple of years, have started using the same risk-avoidance language:

“Licensed properties are more stable.”

“Familiar IP performs better.”

“We need things with built-in audiences.”

“Original projects are harder to sell right now.”

So the pivot begins. More licenses. More recognizable brands. More projects that feel “safe” internally, even if they’re creatively conservative.

And again, the logic isn’t evil. Budgets are tighter. Distribution is fragile. Retail is cautious. Everyone is exhausted. But here’s the problem: safety doesn’t mean sustainability.

For comics, looking “somewhere else” became crowdfunding, now a separate ecosystem all its own, where readers pay $15 or more for a single issue comic! And happily so.

For film/tv, this became streaming, but streaming has since become its own “data-driven” machine, pumping out “content” to align with an algorithm more than stories aligned with unique points of view.

And to make matters worse, there’s the issue of sheer volume. We now have over 7x the number of films available to us to watch on any given day in 2025 than we had in 2005 with DVDs.3 That doesn’t even count short form content.

When storytelling is this prevalent, this ever-present, within a creator economy where so many humans are telling stories of some kind or another, on a planet this full of people and each culture more diverse than ever before - suddenly the homogeniety of these stories sticks out like never before.

If we’re going to make this much content, tell this many stories, spend this much money on doing so for this many people of all stripes of life, how can we justify adhering to our historical relationships with storytelling?

Wanting original stories, from original voices is a rallying cry that creators and audience members are getting behind in the streaming era, and it’s driven in part by the contraction of industries and the “data-driven” tech nature of our modern decision making.

But it’s also pretty clear that downplaying original content for replays, remakes, rehashes, and reimaginings is something we have done for nearly all of human history, barring rare exceptions. We have to learn how to love the new more than the old. How to preserve but not revere. How to be inspired by but not overly influenced by.

It’s not going to be easy. It’s never been our default. Originality seems to be something we have to learn how to value and seek out in an active way.

Compared to today, humans produced only a fraction of the sum total of storytelling, and even that output was heavily tied to previous works and real historical events.

That said, franchises are admittedly more obvious today, and heavily marketed to us than ever before. When Coppola made The Godfather Part II, the studio fought to keep the “Part II” off the title - the wisdom of the time was that no audience would want to watch a “Part II” if they’d already seen a “Part I”. It was such a different time!

By 1990, when Coppola was making Part III, they refused to REMOVE the “Part III” from the title (Coppola wanted to call it “The Death of Michael Corleone”, but the studio was having none of it, successive numbered entries having been proven sales drivers.)

It was less than a decade from The Godfather Part II to Rambo: First Blood Part II and now we don’t even blink at Fast and the Furious Part X Part II. We may never be free of remakes, re-dos, and franchises on the whole, but we can dial back how absolutely we’re clinging to legacy concepts, storylines, and characters.

Yet even this won’t be easy. We have to stop worshipping the old, the known, our childhoods. We have to start loving the future, the new, what comes next. Preservation of media is wonderful, but we have to stop believing that drowning ourselvs in rewatches of what has come before is what cinema is all about.

The more we ourselves lean heavily into supporting the new, the more the culture and therefore the industry will, too. Good luck to us!

Okay, but hear me out, there’s a way to make this amazing: Donnie Yen and Tom Cruise. Paramount already has Cruise’s M:i franchcise. Now but these two geriatric 60-ish year olds who can still kick ass together. It’s geriatric Rush Hour and all about aging franchises and then sure the even older (but no longer kicking ass) Jackie Chan can cameo. It’s perfect. And the very fact that I authentically want this so bad is the problem this article is talking about!

Back in 2005, at the peak of DVD sales, 35,000 movies had been released on the format. Comparatively, there are now over 250,000 movies available to stream on any given day (this includes individual rental and purchase, not just subscription streaming.) That is a difference of epic scale. I wrote more at length about this here,

Movie idea: In the age of the first-ever story, several storytellers race to secure the rights to it. Probably culminates in a battle that's identical to one that happens in said story or something.